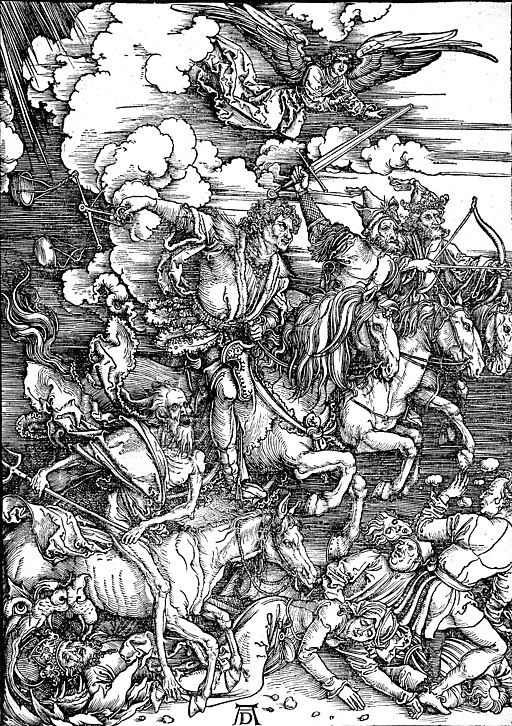

Albrecht Dürer, The Revelation of St John: The Four Riders of

the Apocalypse, 1497-98, Woodcut, 39 x 28 cm, Staatliche Kunsthalle

Et vidi quod aperuisset Agnus unum de septem sigillis, et audivi unum de quattuor animalibus, dicens, tamquam vocem tonitrui: Veni, et vide.

And I saw that the Lamb had opened one of the seven seals. And I heard one of the four living creatures saying, in a voice like thunder: “Draw near and see.”

- Revelation 6:1

Latin Vulgate text, English translation (CPDV)

When the Lamb opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth living creature say, "Come and see!" I looked and there before me was a pale horse! Its rider was named Death, and Hades was following close behind him. They were given power over a fourth of the earth to kill by sword, famine, and plague, and by the wild beasts of the earth.

— Revelation 6:7-8 (NIV)

Resignation was ever the fount of man's strength and new hope. Man accepted the reality of death and built the meaning of his bodily life upon it. He resigned himself to the truth that he had a soul to lose and that there was worse than death, and founded his freedom upon it. He resigns himself, in our time, to the reality of society which means the end of that freedom. ... Uncomplaining acceptance of the reality of society gives man indomitable courage and strength to remove all removable injustice and unfreedom.

- Karl Polyani

On this day, in this week, of horrific killings, probably the last thing most people want to think about is Death, Hades, and the Apocalypse. We want to think of blessed angels (the cherubic kind) and feel the sharp pain of their loss, while doing our best to keep from being engulfed in the horrific images their slaughter brings to mind. Their innocence magnifies that pain, but it also gives us hope. The radiance that surrounds our images of them, before and after death, gives us a glimmer of light in the midst of the darkest of tragedies.

This is as it should be, or at least is the best many of us can muster, while reeling from shock and pain. The only immediate sense to be made of such brutal, heartless, deranged acts is to grasp the good that was lost and embrace all the more those that we love and hold most dear.

But what follows, sooner for some than others, are deeper questions and the pressing need to take action, to do whatever conceivably can be done to keep something like this from happening -- yet again. Hence the talk of gun control, better access to and quality of treatment for mental illness, and help for families with troubled youth. No one expects that any particular measure or measures will prevent all mass killings. Nor does anyone suggest that their implementation, alone, would have averted the tragedies of this past week. What is hoped is that these tragedies will at last bring open-minded and clear-sighted discussion of what reasonably can be done to reduce the extraordinarily high incidence of gun violence in the U.S., which is unparalleled in the world. And what is lamented is things both done and left undone.

None of this -- neither the radiance of angels nor the drive to seek practical solutions -- can ever take us away from the reality of Death, the Pale Rider and his fellows, with Hades following close behind. Death is cruel, whether it comes in a sudden explosion of violence, calamity, or disease, or slowly from infirmity, ending in a last rattling gasp for breath. It is nothing to be sensed or known other than in its gaping, bleeding, ashen loss of the living, breathing flesh that was human. And it always comes, sooner or alter, pounding down the road.

Nevertheless, whether we deal with death in terms of resignation, acceptance, protest or denial, there remains what is "worse than death." In times past when most people saw the End of Times as a prophetic vision of the near future, it was the spectre of Hades, eternal torment and separation from God. Polanyi suggests that this vision may have given those who lived in times and places with little or no hope in their daily lives, a kind of freedom in knowing that they might be saved from "worse than death" for eternity. No matter what horrors The Horsemen brought, no matter how grinding and awful their daily lives, with Death all around, there was still hope of salvation.

Polyani further suggests that this kind of freedom has been lost in modern society but that another kind may be found in the hope that comes from the courage and will to seek to "remove all removable injustice and unfreedom." Secular humanists no doubt would agree, while contemporary mainstream Christians would contend that Kingdom building on earth does not replace hope of eternal salvation but rather is an essential part of that hope, now and in the days to come.

However we might employ systems of thought, such as theology or social or political philosophy, to sort this out, in the end what remains is "worse than death" -- not things that we might imagine are or could be worse than dying, but rather the gut feeling and knowing that there is, indeed, "worse than death."

A tragedy like the killings in Newtown makes no sense, no matter how much we may try to reduce it to a political or social problem or enlarge it to the forces of Evil. There is no picture, no way to conceive of this kind of slaughter of innocents, which has no context. The Four Horsemen do not capture it. Nor is there any social or political context of the kind that would give us some kind of perspective, such as what we have for acts of terrorism, torture, and tyranny.

We must weep. We must mourn. We must comfort the afflicted. This must come first. But we must also dig deep into our incomprehension, pain and search for truth.

There lies our deepest fear: senselessness gripping and grinding us up in its jaws. Freedom from fear requires something other than diving into bunkers, clutching our material belongings, brandishing our guns, and guarding ourselves from the Government, dark-skinned or Spanish-speaking people, or any others whom we think might take our property and guns away. Freedom from fear requires something more than engineering our safety by means of even better lock-down procedures at schools and gun control. Freedom from fear requires searching deeply, thoughtfully, with humility and love, for what gives us the sense of "worse than death," and rejecting the mad, self-centered, self-protecting ways of trying to run ahead of the galloping horses.

We cannot stop the riders but we can slow them down.

This is as it should be, or at least is the best many of us can muster, while reeling from shock and pain. The only immediate sense to be made of such brutal, heartless, deranged acts is to grasp the good that was lost and embrace all the more those that we love and hold most dear.

But what follows, sooner for some than others, are deeper questions and the pressing need to take action, to do whatever conceivably can be done to keep something like this from happening -- yet again. Hence the talk of gun control, better access to and quality of treatment for mental illness, and help for families with troubled youth. No one expects that any particular measure or measures will prevent all mass killings. Nor does anyone suggest that their implementation, alone, would have averted the tragedies of this past week. What is hoped is that these tragedies will at last bring open-minded and clear-sighted discussion of what reasonably can be done to reduce the extraordinarily high incidence of gun violence in the U.S., which is unparalleled in the world. And what is lamented is things both done and left undone.

None of this -- neither the radiance of angels nor the drive to seek practical solutions -- can ever take us away from the reality of Death, the Pale Rider and his fellows, with Hades following close behind. Death is cruel, whether it comes in a sudden explosion of violence, calamity, or disease, or slowly from infirmity, ending in a last rattling gasp for breath. It is nothing to be sensed or known other than in its gaping, bleeding, ashen loss of the living, breathing flesh that was human. And it always comes, sooner or alter, pounding down the road.

Nevertheless, whether we deal with death in terms of resignation, acceptance, protest or denial, there remains what is "worse than death." In times past when most people saw the End of Times as a prophetic vision of the near future, it was the spectre of Hades, eternal torment and separation from God. Polanyi suggests that this vision may have given those who lived in times and places with little or no hope in their daily lives, a kind of freedom in knowing that they might be saved from "worse than death" for eternity. No matter what horrors The Horsemen brought, no matter how grinding and awful their daily lives, with Death all around, there was still hope of salvation.

Polyani further suggests that this kind of freedom has been lost in modern society but that another kind may be found in the hope that comes from the courage and will to seek to "remove all removable injustice and unfreedom." Secular humanists no doubt would agree, while contemporary mainstream Christians would contend that Kingdom building on earth does not replace hope of eternal salvation but rather is an essential part of that hope, now and in the days to come.

However we might employ systems of thought, such as theology or social or political philosophy, to sort this out, in the end what remains is "worse than death" -- not things that we might imagine are or could be worse than dying, but rather the gut feeling and knowing that there is, indeed, "worse than death."

A tragedy like the killings in Newtown makes no sense, no matter how much we may try to reduce it to a political or social problem or enlarge it to the forces of Evil. There is no picture, no way to conceive of this kind of slaughter of innocents, which has no context. The Four Horsemen do not capture it. Nor is there any social or political context of the kind that would give us some kind of perspective, such as what we have for acts of terrorism, torture, and tyranny.

We must weep. We must mourn. We must comfort the afflicted. This must come first. But we must also dig deep into our incomprehension, pain and search for truth.

There lies our deepest fear: senselessness gripping and grinding us up in its jaws. Freedom from fear requires something other than diving into bunkers, clutching our material belongings, brandishing our guns, and guarding ourselves from the Government, dark-skinned or Spanish-speaking people, or any others whom we think might take our property and guns away. Freedom from fear requires something more than engineering our safety by means of even better lock-down procedures at schools and gun control. Freedom from fear requires searching deeply, thoughtfully, with humility and love, for what gives us the sense of "worse than death," and rejecting the mad, self-centered, self-protecting ways of trying to run ahead of the galloping horses.

We cannot stop the riders but we can slow them down.